Nice! exciting to hear about your progress.

I would not downplay your skills at the moment. Maybe it will take 3 more frames till you have confidence, or maybe you are already ready!

From my engineering perspective: the only question you need to ask yourself is: is my frame structurally safe to ride? Everything else: the finish, geometry, marketing, pricing, etc… can be phased in over time.

Since its impossible to test EVERY frame that goes out the door, I think there are two ways to answer the “will my frame explode” question:

- Process Controls

- Field Testing

Process Controls

" Process control is the ability to monitor and adjust a process to give a desired output. It is used in industry to maintain quality and improve performance."

For manufacturing, process controls can be things like ambient temperature, humidity, raw materials source, cleaning schedule, maintenance schedule, etc…

The strength of a steel frame comes down to:

- quality control on your raw materials

- cleaning the tubes for joining

- not overheating the tubes when joining

IMO, the best way to control your process is to build the same style of bike using the same tubes, dropouts, and the same machine setups. This will help you fine-tune your process and build muscle memory. Which degreaser to use, how to calibrate your fixture, which brand of tubes to buy, how much heat is needed, etc… are the process controls that will yield stronger more consistent frames.

Builders like @Meriwether, Curtis (Retrotec), and Rob English make some wild and amazing one-off custom frames every time. But they have years of experience and hundreds of frames under their belt.

Whit’s latest frame is not easy to build and design: https://meriwethercycles.com/2023/03/28/more-of-kurstins-29-torker/

Field Testing

Most failures will come from joining defects or fatigue. Unless you lifetime cycle test every frame that goes out the door, it’s impossible to know if your frame will break. The next best thing is to look at test samples in the field to validate your construction.

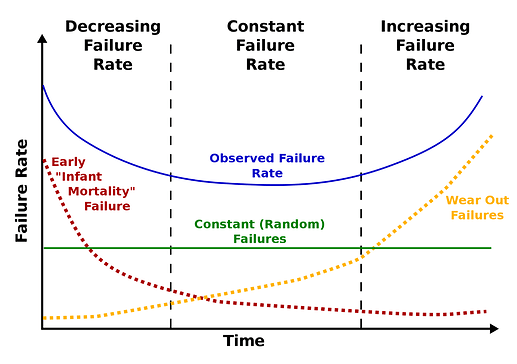

Any product experiences the bathtub of failures:

If you have three bikes that have the same construction and have gotten past the first 6 months of regular riding without experiencing a material, manufacturing, or design flaw, your frames have gotten past the initial failure rate and sitting happily in the bath tub.

Once you are in the bathtub, I think you can have high confidence that your process is good!

Another point that Nick always reminds me: bikes will break. Even the big bike companies, with all their manufacturing and engineering resources, have fork recalls. Every product has a RMA rate which is factored into the cost of buisness. Every builder would be horrified by a minor frame failure, but there is another way you could look at it: every frame has a small chance it can crack, but when working with a custom builder they can repair the frame. And as always, the insurance is not a bad idea, and this thread has become a great resource: Insurance for things you make

@CharlieSBI is there a style of bike you think would suit your potential clients and riding community? I think this is also where the forum can help. There is enough experience here to help design and engineer whatever bike you have in mind. That way you will have confidence that the design is good, and focus purely on the fabrication.