I’m building a wooden bike. The bike will be a personal art project and also a fun machine.

Why Wood?

Of my “maker” hobbies, woodworking is what I’m best at. I’ve welded before, but it’s not my favorite tool in the shop. And while my welds are functional, I feel that the learning curve to get to truly beautiful welds and brazing is very, very steep. I’d need a lot more practice to get to something that I’d be happy looking at.

Secondly, wood is an absolutely beautiful medium that connects directly to why I ride bikes. I live in rural New England, and am surrounded by forest. I do exclusively gravel riding at fat old man speed. Doing that on a bike that I’ve built myself, from wood that was grown in my neighborhood, just adds another layer of satisfaction to that hillclimb through the woods.

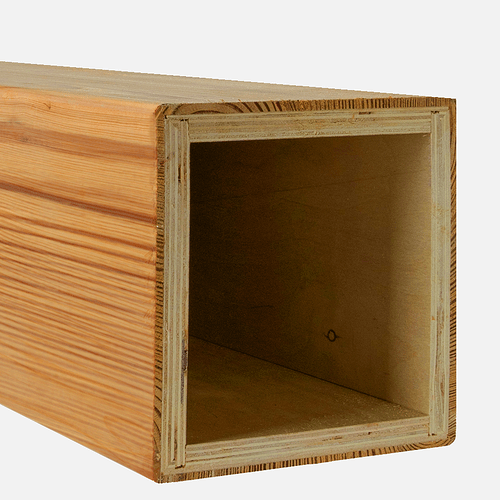

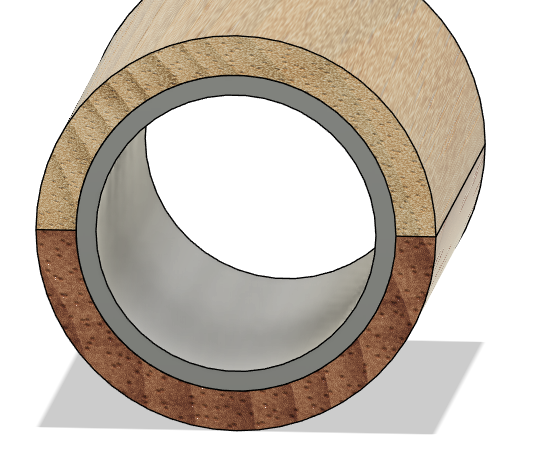

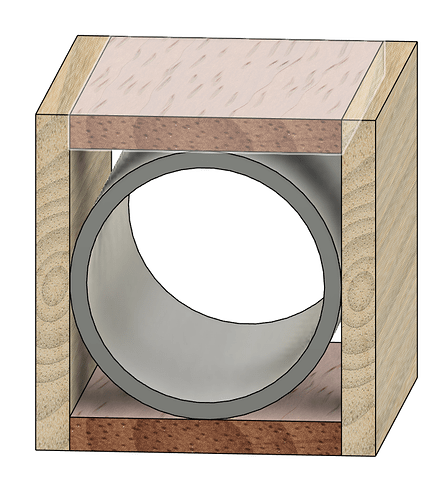

Finally, as proven by the investigations and math of many people who have built wooden bikes before me, wood has great properties for bike building. As nature’s OG carbon fiber, it has natural dampening properties. And depending on species, it has density to strength ratio that is comparable to metals used in traditional bike framebuilding.

Why Bikes?

I’m at the point in my life where what I invest my time in either must make me a pile of money, or produce maximum joy. Obviously building bikes is the path to riches…

For me, the bike project seems like something I can produce time and again in the shop, and each time will be satisfying. Some people produce cutting boards, some furniture. I have another 30 years or so on this earth and am searching for something where I can fiddle away again and again. We’ll give this a try and see if its worth continuing.

My Goals

For the first bike, I have a pretty simple set of design and learning objectives:

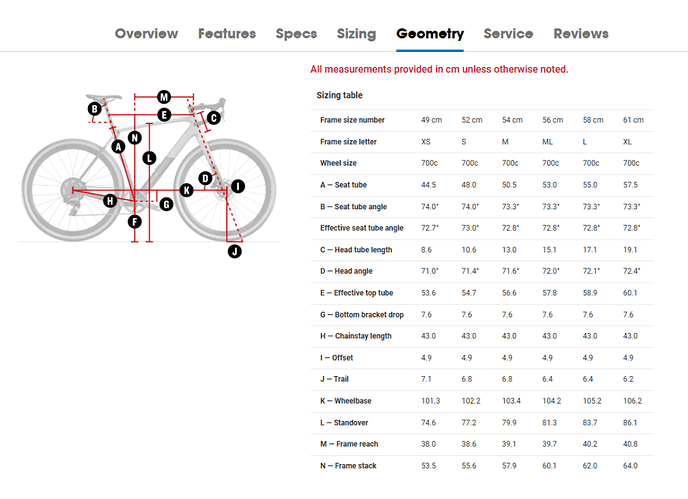

- Build a performance oriented gravel bike under 20 pounds

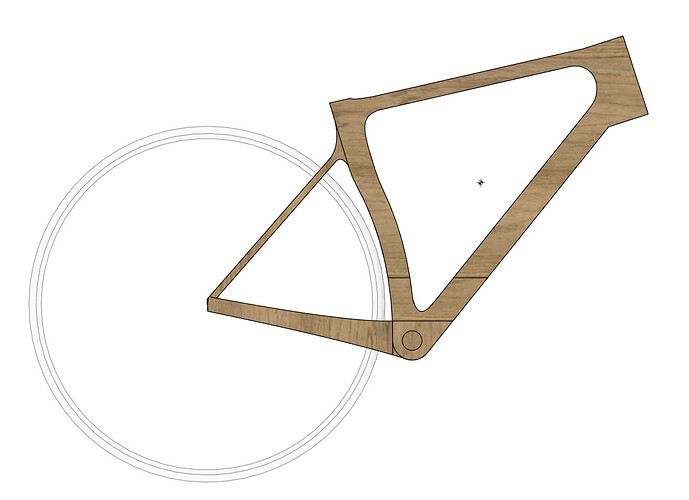

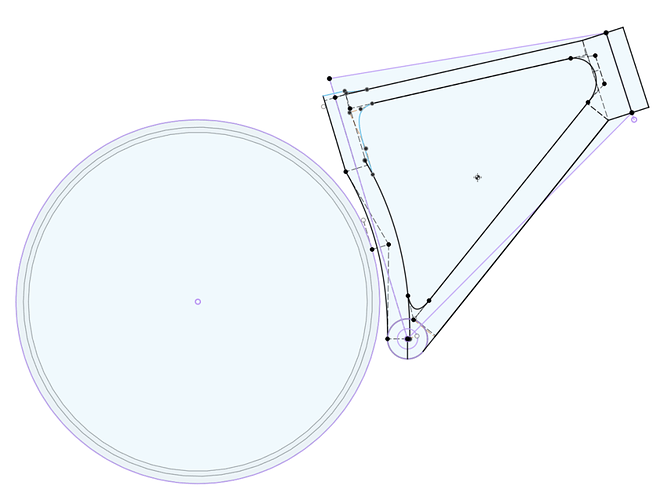

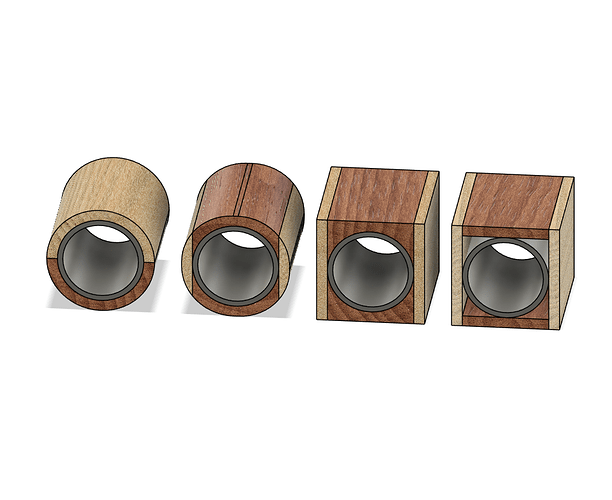

- Learn to draft bikes well in Fusion, building a nicely parameterized model

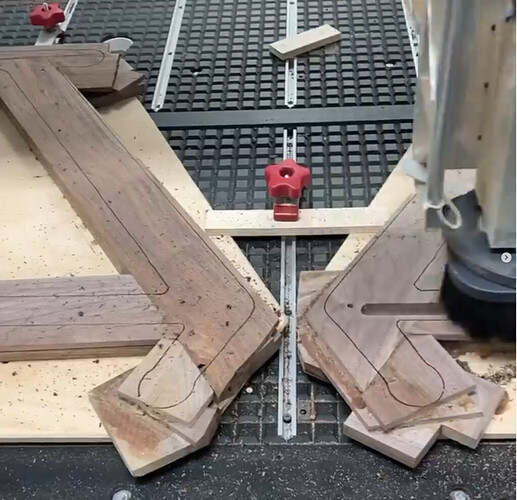

- Develop and test a repeatable construction technique along the way that can be replicated by other home builders

- Document the journey so others can follow

My Approach

My plan is to document this in a step by step fashion here, as well as over on my website Arborvelo.com and potentially on YouTube and Instagram.

The first step is to learn from tons of other great builders out there. I’ll be doing short writeups and lessons learned of other wooden bike building projects here: Wooden Bike Builders. We stand on the shoulders of giants.

I’m also doing a ton of work learning Fusion and getting the initial frame design drafted. I’ll post updates on that soon. Some unbelievable lessons that I’ve seen on here and I will be giving lots of credit as I start posting my drafts.

Definitely want to keep in touch with any other frame builders, so please reach out at matt@arborvelo.com or on this build log. Look forward to sharing the journey!!!